PRESS

Canvas and Crumpets

by Chloe Hyman MAY 3, 2019

Article link here

Superfine! NYC 2019: Dreamscapes and Fractured Figures

CESAR FINAMORI

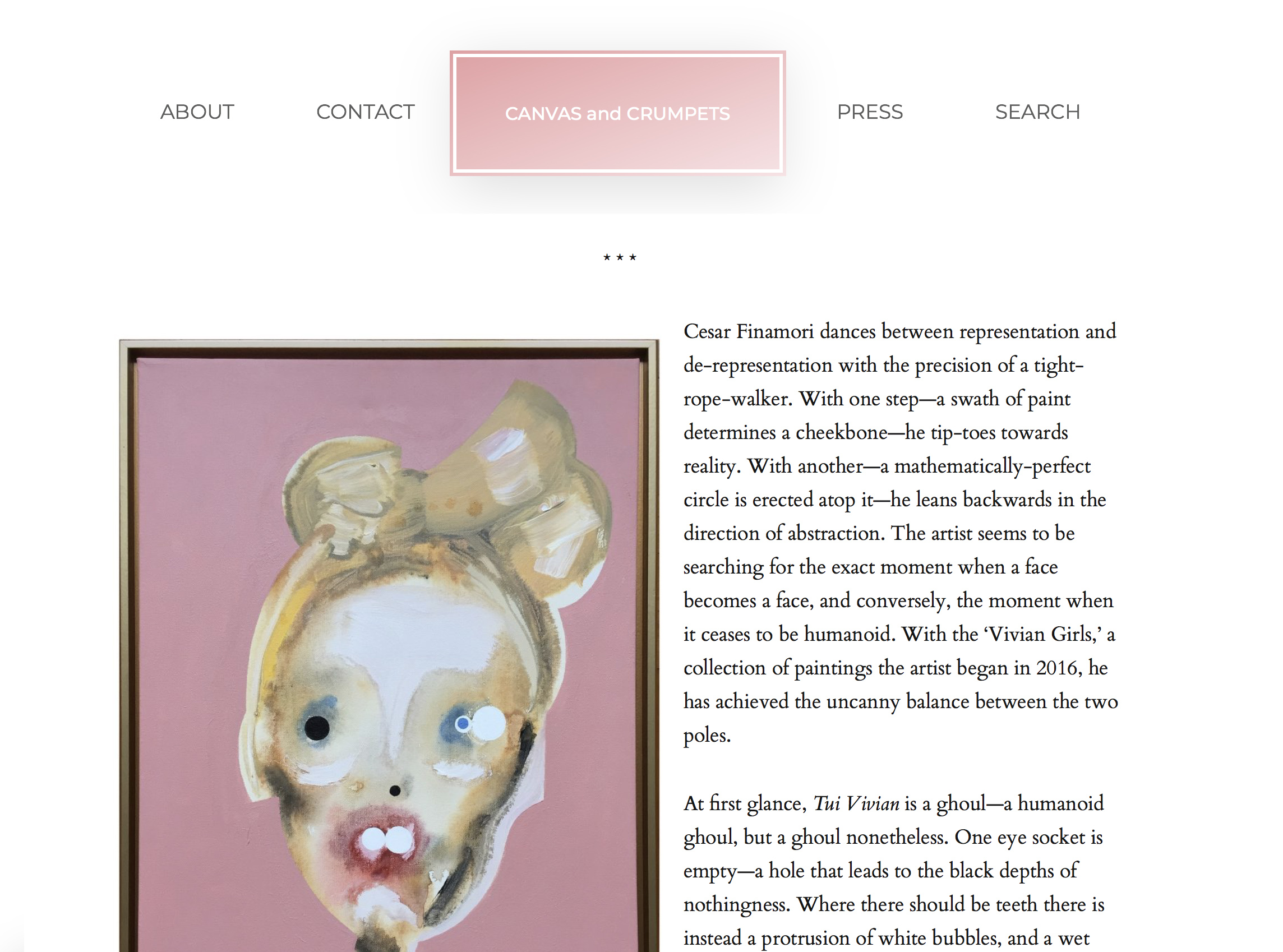

Cesar Finamori dances between representation and de-representation with the precision of a tight-rope-walker. With one step—a swath of paint determines a cheekbone—he tip-toes towards reality. With another—a mathematically-perfect circle is erected atop it—he leans backwards in the direction of abstraction. The artist seems to be searching for the exact moment when a face becomes a face, and conversely, the moment when it ceases to be humanoid. With the ‘Vivian Girls,’ a collection of paintings the artist began in 2016, he has achieved the uncanny balance between the two poles.

At first glance, Tui Vivian is a ghoul—a humanoid ghoul, but a ghoul nonetheless. One eye socket is empty—a hole that leads to the black depths of nothingness. Where there should be teeth there is instead a protrusion of white bubbles, and a wet red ring has formed around her lips. Disembodied from the rest of her figure, her ghastly bulbous head floats in the ether.

But upon looking closer, the essence of Tui Vivian is not so certain. Many of the elements that seem to render her ghoulish are actually very inorganic in structure, suggesting machine-like precision rather than supernatural ectoplasm. The white circles that fill her mouth and the black circle that registers as an empty socket take more from the geometric experiments of Kandinsky and Miró than any figurative painterly precedent. The artist’s ability to utilize abstraction in the service of figuration is a testament to his conceptual talents. From this I gather that Finamori has a much different understanding of what makes anyone alive than our current paradigms of science and culture dictate. Perhaps it is not the number of humanoid facial features that render a figure human, but the capacity to feel emotion. In that sense, Tui Vivian is more human than you or I; she wears her shock, her horror, her death—whatever it is that bled her of her color and robbed her of her body—more clearly than any person I know can express their state of mind without words. “I think my figures are looking to themselves,” Finamori says, cryptically.

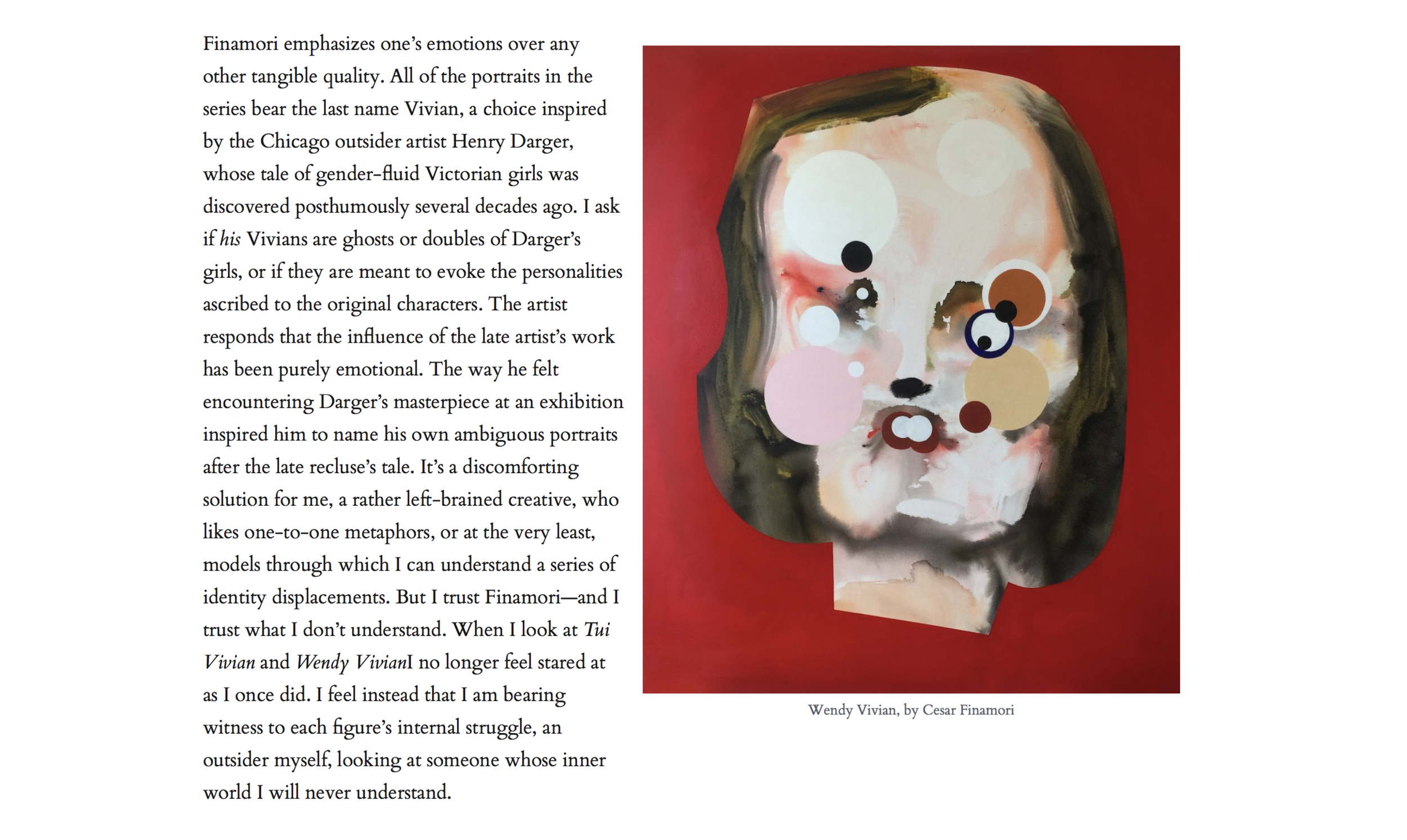

And look they do. The artist’s canvases are dotted with rolling pupils and floating eyeballs– Wendy Vivian is a particularly good example of this tendency. There are so many gaping holes that might be eyes; to which do we look to ascertain the figure’s identity? The eyes are, after all, the window to the soul, the apparatus through which we seek to discover information about those around us. I propose a leading question to the artist: Which of Wendy’s eyes are looking at us? Finamori disagrees with my suggestion that his figures use any of these eyes to consume us. Their action is purely internal, a web of looks exchanged between different sets of eyes—perhaps, I wonder now, different selves within one dominant self.

Finamori emphasizes one’s emotions over any other tangible quality. All of the portraits in the series bear the last name Vivian, a choice inspired by the Chicago outsider artist Henry Darger, whose tale of gender-fluid Victorian girls was discovered posthumously several decades ago. I ask if his Vivians are ghosts or doubles of Darger’s girls, or if they are meant to evoke the personalities ascribed to the original characters. The artist responds that the influence of the late artist’s work has been purely emotional. The way he felt encountering Darger’s masterpiece at an exhibition inspired him to name his own ambiguous portraits after the late recluse’s tale. It’s a discomforting solution for me, a rather left-brained creative, who likes one-to-one metaphors, or at the very least, models through which I can understand a series of identity displacements. But I trust Finamori—and I trust what I don’t understand. When I look at Tui Vivian and Wendy VivianI no longer feel stared at as I once did. I feel instead that I am bearing witness to each figure’s internal struggle, an outsider myself, looking at someone whose inner world I will never understand.

Art Aesthetics Magazine

by D.S. GRAHAMMAY 29, 2017

Link here

Top 5 at The Other Art Fair NYC

CESAR FINAMORI

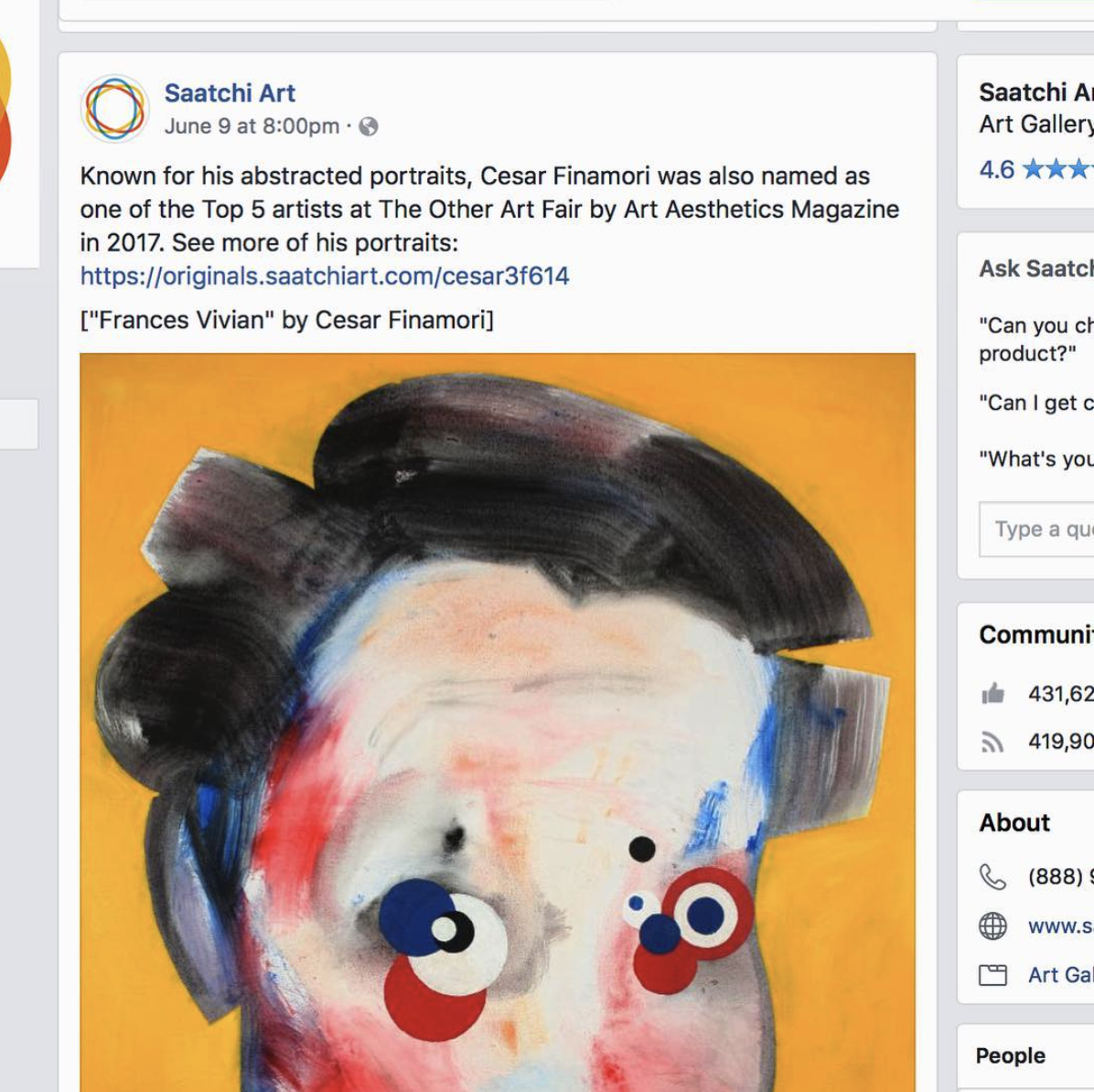

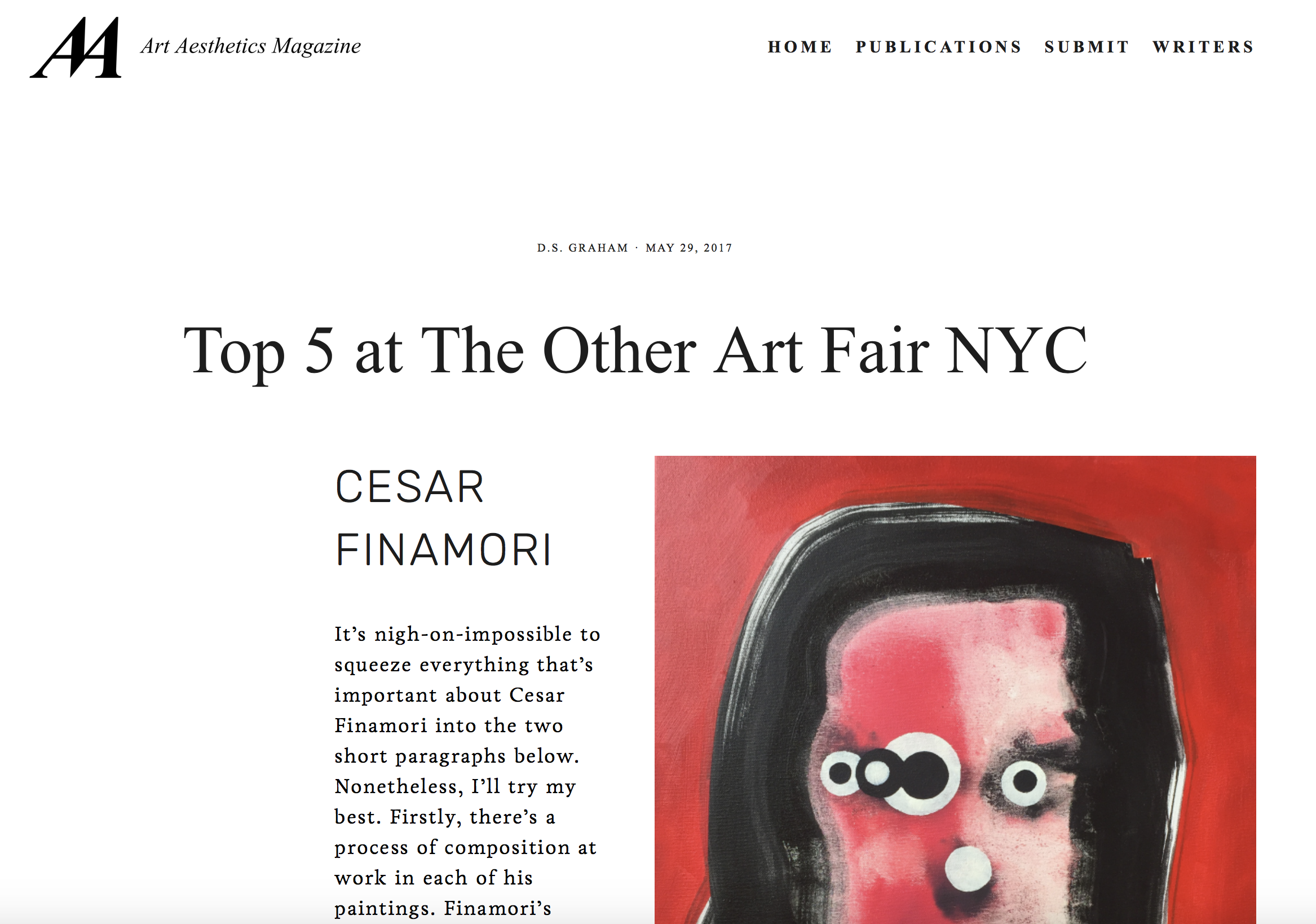

It’s nigh-on-impossible to squeeze everything that’s important about Cesar Finamori into the two short paragraphs below. Nonetheless, I’ll try my best. Firstly, there’s a process of composition at work in each of his paintings. Finamori’s influenced by Henry Darger, the(posthumously) famous exemplar of ‘outside art’ in the twentieth century. Finamori’s fictional sitters’ surnames pay homage to Darger’s In the Realms of the Unreal otherwise known as The Story of the Vivian Girls which was written sometime after 1909 and is yet to be fully published. Darger’s drawings and watercolours were primarily traced from a wide variety of source materials. Finamori’s sketches (which are actually acrylic paintings) are composed of a process by which shapes are both painted and then partially erased to produce the stark lines of the sketch. In this way, there’s something of a homology between Darger—and Yves Klein, another of Finamori’s influences—and the compositional process through which the ‘lines’ of the drawings are thus produced. Secondly, there’s always been something weird about Darger. In fact, many commentators have gone to great lengths to correctly ‘diagnose’ him. Instead of relying upon (notoriously unreliable) psychiatric categories; I’d suggest an aesthetic reading of Finamori’s fictional portraits via Wilhelm Worringer’s well-known Abstraction and Empathy (1907) in relation to Darger, Klein, Matisse. Finamori’s influences often disdained perspective in favour of ‘flattening’ their paintings. ‘Suppression of representation of space was dictated by the urge to abstraction through the mere fact that it is precisely space which links things to one another,’[i] says Worringer. In this way, abstraction is the counter pole to aesthetic empathy and the ‘simple line and its development in purely geometrical regularity was bound to offer the greatest possibility of happiness to the man disquieted by the obscurity and entanglement of phenomena.’[ii] Whereas Darger’s artworks-cum-writings depicted the Vivians against a backdrop of bewildering violence; Finamori’s are depicted against a backdrop of ‘action painting’ intimating violence. Crucially, their essential features are then entirely abstracted…

Finamori’s fictional portraits are still portraiture. His painted visages suggest its rhyming connotation. And yet, it’s still a recognisable face. However, it’s form has become more fantasy and more mirage. It’s more inchoate and nebulous than defined. And yet, the eyes, noses, and nostrils have become more and more defined. In fact, they’ve become too defined, too precise, and too abstract. For they’re no longer eyes, noses, and nostrils. Instead, they’ve become pure circles, pure voids. Perhaps, pure machine? Or perhaps, they’ve become petri dishes spawning other petri dishes. If so, Finamori’s not interested in their amoeba or bacteria. He’s interested in the petri dish itself. Indeed, the pure circular forms of the eyes, noses, and nostrils spread out and colonise the vague visage of what was once the subject’s face. There’s something mechanical about their progress… I’ve got to move onto discussing the other artists. It’s obvious however, that Finamori is possessed of a rare and visually striking talent.

[i] Wilhelm Worringer, Abstraction and Empathy, trans. by Michael Bullock, (Chicago: Elephant, 1997), p.22

[ii] Ibid, p.2

Artchive.ru

by Ivan Markovsky

Wrap my new art, please!

Cesar Finamori (New York, USA)

At first,those bright female portraits look like pop art exercises which they are definitely not. Note the titles. «Debbie Vivian», «Peggy Vivian», «Elise Vivian», «Eve Vivian». They refer to ‘In the Realms of the Unreal'(‘The Story of the Vivian Girls'), the illustrated manuscript byHenry Darger(1892−1973), one of the most celebrated outsider artists.

Then look at their faces.

«Finamori's fictional portraits are still portraiture. His painted visages suggest its rhyming connotation. And yet,it’s still a recognizable face.(…)The eyes,noses,and nostrils have become more and more defined. In fact,they’ve become too defined,too precise,and too abstract. For they’re no longer eyes,noses,and nostrils. Instead,they’ve become pure circles,pure voids»

-wrote D.S. Graham in his review.

The longer you look at these pictures the more interesting things they tell you.